"No justification moral or legal": Black WWII soldiers and the threats at home

On June 25, 1941, six months before the United States entered World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt recognized that issues of discrimination and segregation would impede the coming war effort. With Executive Order 8802, he banned discrimination by federal agencies or companies involved in defense work. But the order did little to protect Black enlisted men, who were relegated to restricted roles within segregated units. When assigned to bases in the South, these troops had to navigate segregation laws dictating their behavior off-base as well.

On February 1, 1942, Thomas E. Broadus, a 26-year-old Army private from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, was off base enjoying the weekend in Baltimore when he was killed by a Baltimore police officer. The War Department investigated the case but never pursued a prosecution. Broadus’s death became one of the many instances that symbolized the plight of Black servicemen and the perils of segregation during WWII.

In response to the incident, as well as others like it across the South, civilians wrote letters to government officials, expressing concern about the treatment of Black servicemen who were defending the nation. In some letters, writers highlighted the combustible potential of sending Black men from the North into the Jim Crow South. Attached to these letters were newspaper clippings from all over the country that recounted alarming events of violence towards Black enlisted men.

In a February 20, 1942, letter to Roosevelt, Pittsburgh resident Estella Washington emphasized the plight of Black citizens in the enlisted services. She touched on the Broadus case, as well as an incident from January 10, 1942, when at least ten Black soldiers were killed by civilian and military law enforcement in Alexandria, Louisiana. Washington wrote: “Yes, our men are full of patriotism, American negroe soldiers, only to meet death because they are negroes before they reach the battle fields. And what do they get? Nothing. There are offices in Army that the negroe can never hold. In defending America if there is a hero his name is never called.” The government’s response to letters such as Washington’s was brief – an acknowledgment of the letter and, occasionally, an indication that the matter was either under consideration or already addressed within the military apparatus.

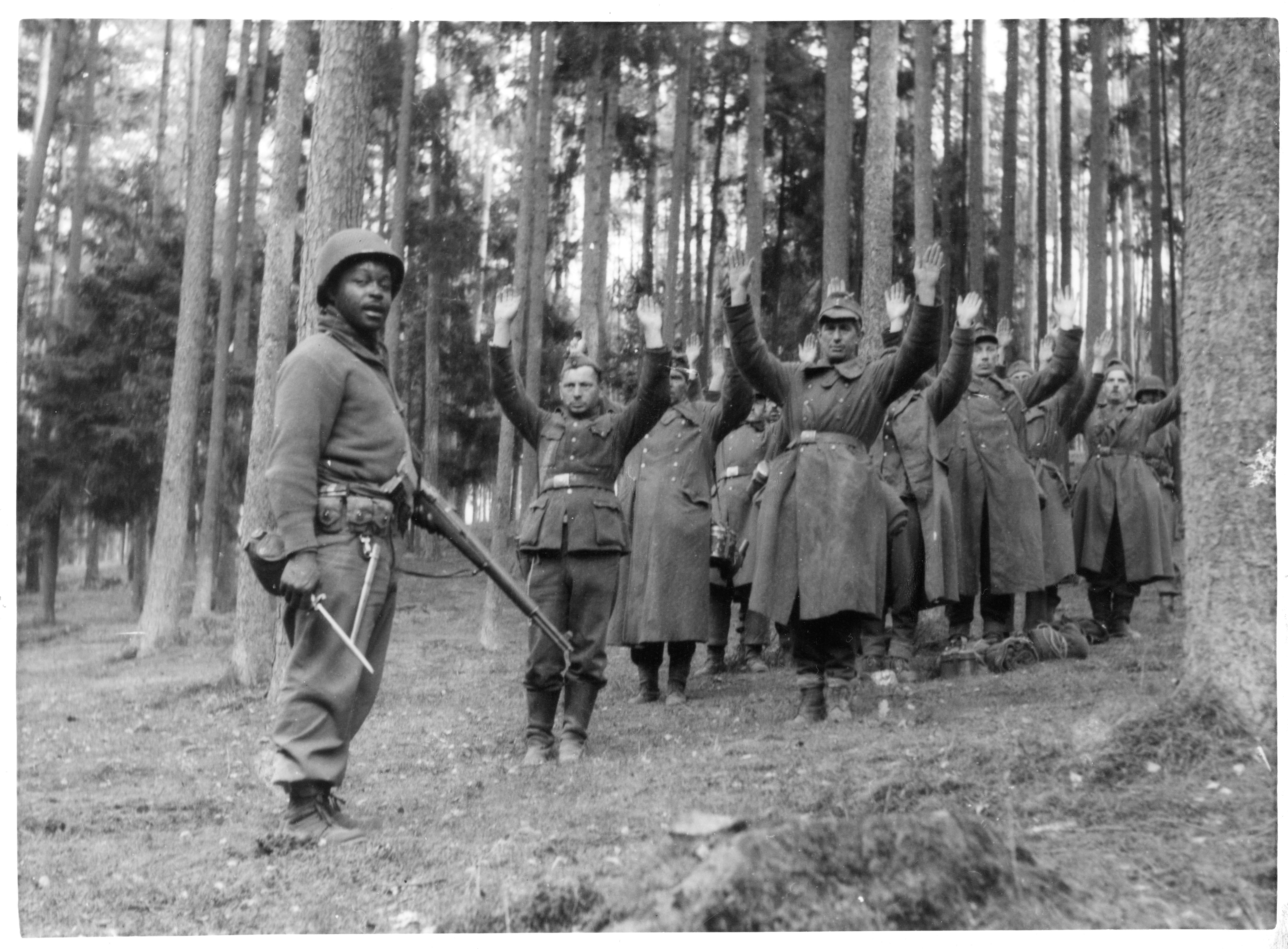

Throughout the South, clashes between white law enforcement and Black soldiers raised concerns from letter writers about how Axis propaganda might capitalize on domestic unrest. At the same time, Black men continued to seek out opportunities to enlist and fight for their country. In a February 16, 1942, letter to Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of War, Charles G. Baugh, a Black man, expressed interest in joining the new U.S. Air Corps. Due to segregation in the military, the Air Corps restricted the number of training spots available for Black men. Roy Wilkins, assistant secretary of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), recommended that men interested in joining the Air Corps be admitted to the program regardless of race.

More than two years after the killing of Broadus, violence and discrimination against Black soldiers in the U.S. continued with few or no consequences. On March 13, 1944, Private Edward Green was fatally shot by an Alexandria, Louisiana city bus driver after Green sat in a “whites only” section of the bus. The NAACP wrote to the War Department demanding an investigation. Although the War Department acknowledged that there was “no justification moral or legal” for the killing of Green, it stated that it had no jurisdiction to act since the killing occurred outside a military base. Officials referred the incident to the Department of Justice (DOJ), which similarly cited a lack of jurisdiction.

In a letter to Assistant Attorney General Tom C. Clark dated May 5, 1944, Thurgood Marshall referenced the fatal shooting of Private Raymond Carr, in December 1942 – also in Alexandria, Louisiana. Raymond Carr was killed in 1942 by state trooper Dalton McCullon in Alexandria. Carr was on duty, policing in the downtown area, when he was knocked down by a state trooper and shot by McCullon. He died four days later in a hospital. A state grand jury declined to proceed against the state officers. Similar to Broadus and Green, the cases were not pursued by the federal government.

In his letter, Marshall cited the “numerous killings of Negro soldiers by civilians and civilian police. There have been many more instances of severe beatings of Negro soldiers in certain areas in the South. We are not aware of a single instance of prosecution or of any steps being taken by the Federal Government to either punish the guilty parties or to prevent the recurrence of these crimes against the uniform of the United States Army.”