A class project that took years -- and ended up on the President's desk

Ten years ago, the students in Stu Wexler’s high school Advanced Placement Government class in Hightstown, New Jersey, had a problem. As part of their course work, they were researching cold cases from the civil rights era, but when they requested records from the federal government through the Freedom of Information Act, the documents would often come back with large sections redacted.

It was frustrating, as Oslene Johnson recalls. Johnson and other students were researching the 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, which killed four girls. For Johnson, a young Black woman herself, the image of those four girls walking up the church steps stuck with her. “It was a personal touchstone,” she says, “and why I cared so much about this immediately.” But even though that case had led to two trials – and two convictions – in the early 2000s, Johnson was still staring at a lot of pages that were blacked out.

The students got to talking. How, they wondered, could they even begin to understand the story behind these cases when key information within the records was being withheld? But there was a possible solution. Back in 1992, Congress had authorized the creation of a review board charged with expediting the release of investigative records surrounding the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. And in 2006, the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act had re-opened dozens of cases from the civil rights era.

To Johnson and the other students, the “amount of care and attention given to records around a presidential assassination is just as important to civil rights cold cases,” she says.

And that’s when things got interesting. Wexler taught two government classes that year, and students in both classrooms rallied around a bold idea – to propose congressional legislation that would expedite the release of records from civil rights cold cases. And what would occur over the next several years – as the effort took on momentum within the halls of Congress, and ultimately to the desk of the president – was that the Hightstown High School students were not just learning history, they were making it.

“We didn’t have to learn how a bill became law,” says Lydia Francouer, one of the students. “We were living it.”

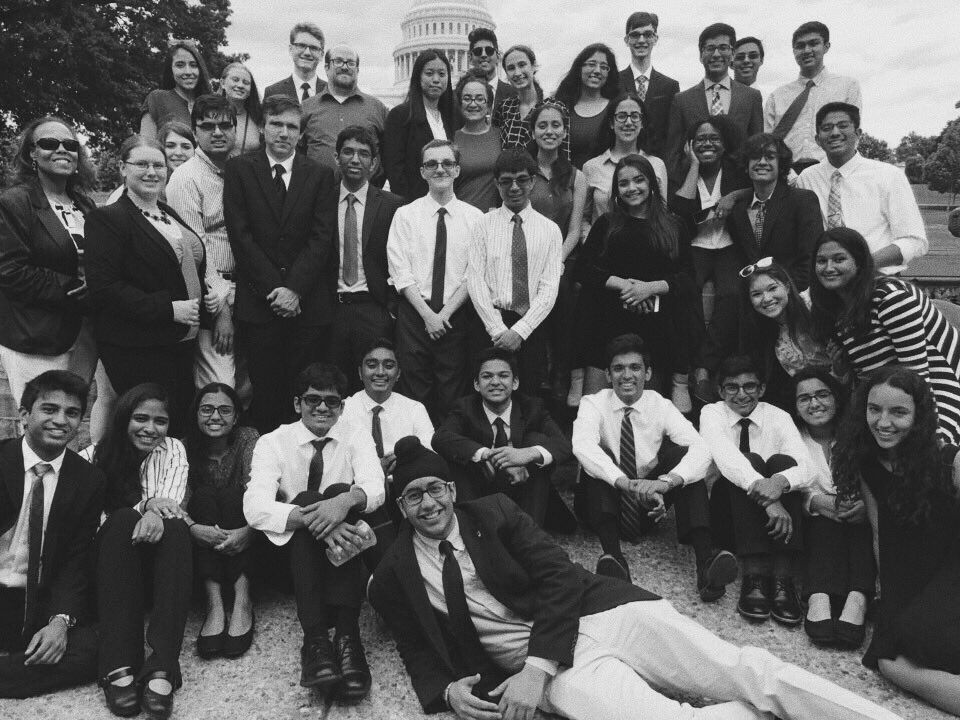

The JFK assassination records legislation was their inspiration. They used the language from that bill as their template, then began shopping the idea around to federal lawmakers. The students found a receptive audience in Bobby Rush, then an Illinois congressman. They made field trips to Washington, D.C. And when they met with legislators, Wexler purposely waited in the lobby while his students took the meeting. This was their initiative, he told them, not his. They were tactical and organized – students were assigned different roles, such as media outreach, lobbying, social media, and researching cold cases specific to the districts of each representative they spoke with. “We weren’t naive enough to forget we were high school students," Johnson says. "So we knew we had to be more prepared than anyone thought we would be.”

Months passed. Final exams came and went. New students arrived in the AP Government class. And they took up the cause, lobbying, finding new congressional support, and spreading the word. With each successive class, everyone had to buy in on the efforts. In this way, the movement to author a bill, then to lobby for it and guide it through the halls of Congress, became the work of dozens of students who were years apart.

And for many students, just because they graduated and moved on to new chapters didn’t mean they forgot about the efforts. In the fall of 2016, Jay Vaingankar was a freshman at the University of Pennsylvania. He made a trip to D.C. to Rush’s office, where he went through the legislation line by line with the congressman’s team. If he felt intimidated by his youth and inexperience, Vaingankar made sure not to show it.

“We weren’t going to sit back and wait our turn,” he says. “I’d show up in D.C. in a suit, tie, and American flag pin. I learned that if you take yourself seriously, other people will take you seriously.”

In the Senate, Alabama Senator Doug Jones, who’d prosecuted the 16th Street Baptist Church bombings as a U.S. attorney years earlier took up the banner as a sponsor in the Senate. He made an impassioned speech on the Senate floor, and Senator Ted Cruz of Texas heard it and signed on as a co-sponsor. The bill now had momentum in both houses. And then, in late 2018, it passed.

But it still needed the signature of the president. Worried about a pocket veto – when legislation passed by both houses dies for lack of signature in the White House – the students took to social media. And on Jan. 8, 2019, President Trump signed into law the Civil Rights Cold Case Records Collection Act.

But even that wasn’t the end of the students’ work. They kept lobbying – that Congress appropriate funds for the Board to be established and start its work, that the members themselves be appointed and confirmed. Today many of the former students of Wexler’s AP Government classes at Highstown High School are still active – promoting the work of the Board and lobbying on behalf of continued efforts to open up the federal records on civil rights cold cases.

“The focus has always been on the families of the victims,” Francouer says. “A lot of family members are getting older and time is running out to give them some closure, as well as provide a historical chronicle in terms of what happened to their family member.”

For the current Board members – who released their first tranche of cases last October, with hundreds more in the pipeline – the role of the Highstown High School students can’t be overstated. “The reason we’re able to do this work – the important work of shedding light on a dark chapter in our nation’s history – is because of the efforts of these students,” says Board co-chair Margaret Burnham. “We wouldn’t be here without them.”